Employers in England are being encouraged to reopen their workplaces to staff who cannot work from home, while those in other parts of the UK are likely to be making plans ahead of similar moves. The guidelines are changing on a weekly basis, but here are eight challenges that have been identified by XpertHR, that you might need to consider, regarding bringing your staff back and keeping them all safe.

Continue readingCategory Archives: Wellbeing

Managing Mental Wellbeing in the Workplace – Part Three: Return to Work

Having good mental health in the workplace is a vast subject, which is why I split it into three separate posts. In Part One, I wrote about the importance of providing good training and resources for line managers. Part Two covered managing absence.

This final blog in the series takes you through what you need to consider when an employee is returning to work.

Adjustments at Work

On drawing up the action plan, an honest dialogue between the parties involved must be had about what adjustments your organisation can and cannot make in terms of the employee’s job and tasks.

It is important that you are guided by the individual experiencing the mental health problem. Explore their specific needs and be as creative as possible in addressing them. Make it clear to them if certain adjustments are not permanent but being made to facilitate a return to work.

Adjustments for employees with mental health problems are often simple, practical and cost effective. Organisational adjustments can include:

- flexible hours or different start/finish times (for a shift worker, not working nights or splitting up days off to break up the working week)

- a change of workspace, for example a quieter working environment

- working from home – you must have regular phone catch-ups to remain connected and prevent the employee from feeling isolated

- changes to break times

- provision of a quiet room

- a light-box or a desk with more natural light for someone with seasonal depression;

- a phased return

- relaxing absence rules and limits around disability-related sickness absence

- agreement to give the employee leave at short notice, and time off for mental health related appointments, such as therapy and counselling.

Changes to the role itself include:

- the reallocation of some tasks

- changes to the employee’s job description and duties

- changes to targets or objectives

- changes to aspects of work that may trigger a mental health problem, such as reducing the amount of time spent on public-facing activities.

If returning the employee to their original role is deemed too difficult, it is vital to involve them in any practical alternative discussions, such as transferring to a different role, or relocation within the organisation. Use the organisation’s agreed procedures to manage these more complex cases, and include HR and occupational health advice.

Practices to support employees returning to work include:

- increased support from the manager, e.g. monitoring workload to prevent overworking

- extra training, coaching or mentoring

- extra help with managing and negotiating workload

- more feedback

- debriefing sessions after handling difficult calls, customers or tasks

- a mentor or “buddy” system (formal or informal)

- mediation, for example where there are difficulties between colleagues

- access to a mental health support group or disability network group

- information on internal support available for self-referral

- identifying a “safe space” in the workplace where they can have some time out, contact their buddy or other sources of support, and access self-help

- provide self-help information and share approaches and adjustments that were effective in supporting others

- encourage building up resilience and following practices that support good mental health, such as taking exercise, meditating and eating healthily

- encourage more awareness of their mental state and the factors in the workplace that affect it

- provide regular opportunities to discuss, review and reflect on their positive achievements to help build self-esteem.

Returning to work after mental health absence can be very difficult; HR and managers should ensure that employees feel comfortable and, especially, do not face unrealistic demands or a huge backlog of work on their return. Make sure that there is plenty of time for informal conversations about progress; an “open door” approach should help employees feel comfortable discussing their situation.

Do you have a question about managing mental health absence in your business? Do call me on 0118 940 3032 or click here to email me.

* This blog is an edited version of an excerpt of an article by XpertHR – Managing Mental Health.

Managing Mental Wellbeing in the Workplace – Part Two: Managing Absence

Having good mental health in the workplace is a vast subject, which is why I split it into three separate posts. In Part One, I wrote about the importance of providing good training and resources for line managers, as well as preventative measures, and how to intervene, provide support and signpost for outside help when needed.

This blog focuses on managing absence part three will look at the return to work.

Maintaining Contact with an Absent Employee

It’s important to keep in touch with any employee who is on long-term absence. But it is vital in the case of someone who is absent because of mental ill health. Maintaining contact can help prevent the individual from feeling isolated, and most people will be very grateful for that.

Your Sickness Absence policy and procedure should set the ground rules for making managing absence easier for all. It should state that:

- employees have a responsibility to stay in contact when they are off sick

- if employees don’t respond to reasonable attempts at contact, the organisation cannot be expected to be aware of, or make adjustments for, their health condition on return to work

- flexibility around contact frequency is necessary, as what is appropriate for an employee absent with a mental health problem may differ from what is appropriate for an employee absent with a physical illness

- encourage line managers to keep in touch with absent employees, emphasising that staying in touch with people who are off sick with mental ill health helps make their eventual rehabilitation and return to work easier for them

- employees should be allowed to have contact with the HR department or another nominated individual rather than by their line manager where appropriate, for example if the employee perceives that the line manager is a contributing factor to his or her ill health

- the organisation and employee should agree a method of communication; often, employees absent with mental ill health prefer to communicate via email rather than by telephone or face to face. If occupational health need to assess the employee, or the employee requests a visit, home visits can be undertaken after a risk assessment has been carried out

- inform the employee about any available support, such as an employee assistance programme or occupational health service, and gain the employee’s permission for these services to get in contact

- employees should not be contacted by other colleagues about work-related issues during their absence, nor be expected to check work emails or voicemail

- a record should be kept of all contact with the absent employee.

Dialogue with the absent employee should be started as soon as possible, either by the line manager or the designated person, and maintained throughout the employee’s absence. These are excellent opportunities to tell the employee about work, and to reassure him or her that the organisation will support them during their absence and return to work.

You may need to adopt a slightly different approach to maintaining contact with an employee who is experiencing a serious mental health problem. Electing to maintain contact with the employee through a representative may be the most effective approach.

If your absent employee’s colleagues would like to get in touch with them, just as with a physical health problem, most people with mental health illnesses appreciate enquiries about their wellbeing. Initially, ask your absent employee what their wishes are in this regard, and what they would like you to convey about their sickness absence to colleagues.

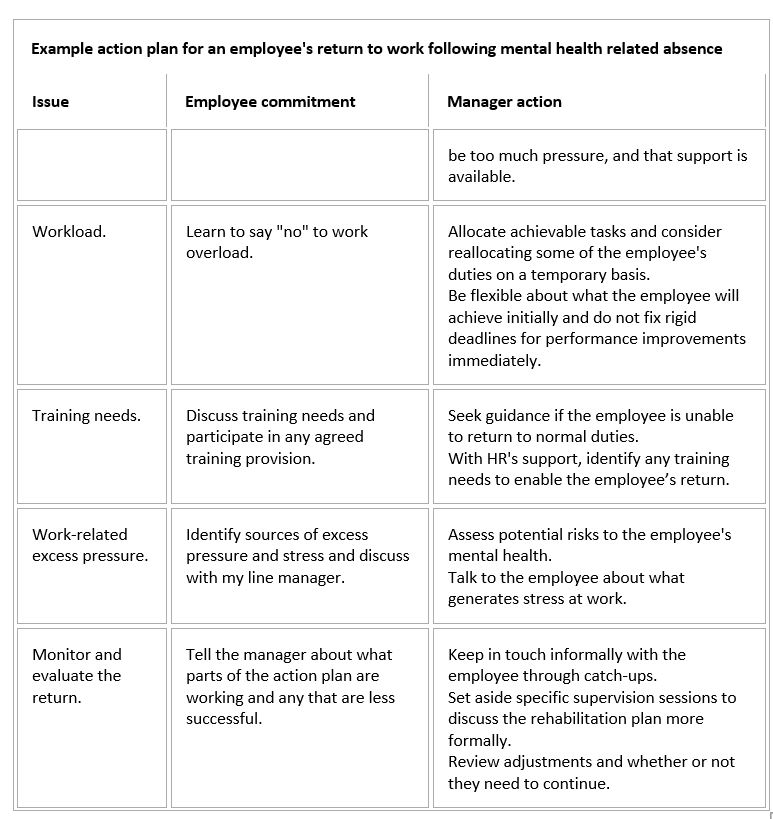

Action Plans

It is vital that an employee’s return to work is managed well, especially when absence was due to mental ill health. A lack of support and poor communication are the most frequently cited issues to an effective return to work.

Develop an action plan prior to the employee’s return to help reassure them that their needs will be met. This typically involves the following:

- assemble a multi-disciplinary team that includes the employee, his or her line manager, and any specialist treatment agencies

- the line manager should agree the action plan and will be responsible for any adjustments agreed, even if discussions were with another nominated individual

- be guided by the employee on when they wish to return to work, and put in place any reasonable adjustments to support this

- an early return to work can help in the rehabilitation of employees who are not yet 100% fit; this can be facilitated by practices such as phased return to work

- the action plan should address the employee’s health needs both for returning to work and on an ongoing basis

- include agreed steps for the employee and manager to take, such as return to work adjustments and ongoing support, reviewing them regularly

- set out expectations clearly to prevent misunderstandings, such as a realistic timetable for a return to normal duties.

Ensure that the action plan is flexible – mental health conditions fluctuate, and recovery can be a rocky road. The manager must patiently support the employee well beyond the first few weeks after return to work. When reviewing progress, adjust the employee’s workload as needed, for example by allocating fewer tasks or allowing longer deadlines.

HR and occupational health may need to provide guidance to managers to support them monitor the health and wellbeing of returning employees.

As there is a lot to take in here, I’ll cover what you need to do next, in order to ensure a smooth return to work for your employees, in the final part of this blog series.

In the meantime, if you have any further queries on managing mental health absence in the workplace, do call me on 0118 940 3032 or click here to email me.

* This blog is an edited version of an excerpt of an article by XpertHR – Managing Mental Health.

Managing Mental Wellbeing in the Workplace – Part One: Guidance and Training for Line Managers

Last month I wrote about the importance of having wellbeing programmes in place, and how it can help employees feel engaged, increase productivity and reduce absence. Linked to that is the importance of managing mental health issues that may arise, including implementing ways to help reduce the chances of mental health (MH) problems occurring.

Managers have a crucial role in managing MH. A negative, unorganised and inconsistent manager may have a detrimental effect on people’s mental health, whereas a supportive manager with strong leadership can help your teams feel valued and recognised.

It is important to remember that just because someone has a MH illness does not mean they cannot perform as well as their colleagues. Often, people with MH conditions are high performers and achievers.

Because the manager’s role in supporting good mental health in the workplace is so crucial, it’s important to provide excellent training and develop a Mental Health Policy for managers to refer to. Guidance should state that:

- Managers are not expected to diagnose but should seek advice from Human Resources (HR) or Occupational Health (OH) if they have any concerns about an employee.

- Approach all aspects of a person’s MH as you would for any other kind of health-related problem, including sickness absence, assessing fitness for work using specialist advice, considering workplace adjustments, and managing performance.

Prevention, Intervention and Support

Provide your managers with the necessary resources to help prevent employees develop work-related stress and to support employees with MH conditions. Each level of intervention includes:

- Primary

Prevention

- Creating a workplace environment that is conducive to good MH, including training line managers in the soft skills needed to encourage disclosure of any MH problems

- Job design – creating work that is satisfying and not excessively pressurised

- Removal of risk factors, including bullying and harassment

- Promoting good working relationships.

- Secondary

Intervention

- Providing support to employees at an early stage of any MH problems, such as stress management and resilience training

- Help line managers to spot when a team member may be struggling with stress or any kind of distress.

- Tertiary

Level Support

- Support your managers in identifying and supporting employees with severe mental ill health by providing mental health first-aid training, guidance on using the management support part of your Employee Assistance Programme (EAP), and training in making effective referrals to OH or other medical specialists

- Employees with more serious long-term illnesses will often need a different management approach, particularly where the condition includes relapses and remission periods. Most employees with enduring mental ill health will generally function well when given support, which also helps them to quickly divulge when they identify the early warning signs that they are not well. That vital workplace support helps to empower them to manage their situation at work.

- Therapeutic

Support

- Regularly promote the support available through your EAP or any external programme, especially therapies for common MH problems, such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

- When referring employees for counselling or CBT, always ensure that they are equipped to handle employees with MH issues

- CBT is recognised as being effective in helping people back to work following MH problems as work-focused goals and strategies can be set, which employees often find empowering. CBT is typically delivered in six to eight sessions of counselling, either face to face or via online e-therapy programmes.

Building Resilience

Building employee resilience makes good business sense – resilient employees are better able to maintain their performance at work, even under pressure. However, keep in mind that many instances of stress and distress are symptomatic of wider problems, which would need investigating. Resilience training would not correct those problems.

Training individuals and teams to become more resilient is particularly important where change has the potential to undermine confidence and morale. Resilience training can also help employees to:

- Be more flexible about organisational change

- Adopt a “can-do” attitude and be more optimistic about their future at work

- Remain calm under pressure and feel less anxious about work and home life.

Encouraging Disclosure About a Mental Health condition

Often, people are reluctant to disclose that they have a MH condition. Mental ill health is a sensitive issue, but most employees welcome an open and honest approach. Ensure your managers have regular catch-up sessions with their teams. Use simple, non-judgmental questions – this helps employees to talk openly and helps managers to spot signs of trouble early. Building a good rapport makes it easier for employees to disclose a MH problem.

Making Timely Referrals to Occupational Health

Referrals to OH may be triggered under various circumstances, including changes in behaviour or sickness absence that may be related to an underlying MH problem, or if the employee’s MH problem is work related. Sometimes, a situation at work may affect an employee’s MH, for example difficult relationships with colleagues.

Where an employee discloses a MH problem, encourage them to consult their GP first, and inform them of support available through your EAP or any other service.

Early referral to appropriate medical and/or specialist services help to nip things in the bud and prevent sickness absence. Therefore, an effective process should include:

- Making referrals as soon as there is a concern about an employee

- Provide OH with background information, including the employee’s job role, any workplace adjustments in place or attempted, whether a disciplinary or performance management process is under way, and whether there are any relationship problems with colleagues

- Asking the OH team relevant questions, e.g. about the individual’s fitness to carry out particular tasks, or the prognosis for a return to work (if the employee is absent)

- Discuss the advice received from OH with the employee as a precursor to building an action plan to help them remain in or return to work.

Encourage your managers to seek expert advice if they feel unsure, or if it is a particularly complex case. Advice could come from OH, HR, or external organisations such as mental health charities.

Feedback following a referral usually provides recommendations and advice about whether the health problem is likely to have an impact on the employee’s fitness to carry out his or her role. If the employee is absent from work, it should also give some idea about how long the absence is likely to last.

All parties must ensure that personal data, including information about individuals’ health, is handled in accordance with your GDPR policy. For instance, if OH needs to liaise with employees’ medical practitioners. You need a consistent approach for when a medical report is requested, who will request it, and how.

Case Management

Always use a case management approach when supporting employees with MH problems to return to, or stay in, work. This approach involves key functions – such as line managers, HR and OH – monitoring the employee’s situation and requirements, and liaising with one another about appropriate actions. Tailor your approach to the employee, as everyone’s mental ill health and their coping mechanisms are unique. Each case should be handled by a consistent group of people, including a single case manager to coordinate all actions.

Training Line Managers

Line managers need training to spot the common signs of mental ill health and to identify employees who are struggling. Training should cover how pressure can become negative stress and other work-related problems, such as poor performance. It should guide managers on how and when to seek specialist help if they cannot deal with, or do not feel comfortable, in managing the issue.

Training line managers should lead to:

- Greater confidence in approaching employees to offer early support at work

- More effective and timely referrals to OH or other specialist services

- More effective management support for absent individuals

- Less stigma about mental ill health at work

- A reduction in absence because of an increased ability to keep employees well at work.

The following areas should be covered in your training provision:

- Being Aware of Potential Triggers, including recognising MH problems. Managers should be alert to work-related factors that can adversely affect employees (see Environmental risk factors).

- Identifying Mental Ill Health. Line managers who know their staff and regularly hold catch-ups are well placed to spot any signs of stress or mental ill health at an early stage. Often, the key is a change in typical behaviour. Symptoms vary, as everyone’s mental ill health is different, but potential indicators are provided in the table below. However, these signs don’t automatically mean that the employee has a MH problem – it could be a sign of another health issue or something else entirely. Training should stress that managers should never make assumptions, and to talk to employees directly.

- Mental Health First-Aid Training. Designed to help managers successfully intervene when a crisis situation at work arises, such as when an individual may be a danger to themselves or others. These courses also cover dealing with panic attacks, acute stress reactions and conditions such as schizophrenia.

- Absence Management and Referrals. Training managers to hold difficult or sensitive conversations with employees will help them to manage absence and specialist referrals. This training should focus on making such discussions open and positive, so that both parties can explore issues freely. The training should emphasise that you do not expect managers to act as a doctor, but to understand when to involve HR or OH professionals.

- Return to Work. Managers need to understand the importance of keeping in contact with absent employees experiencing a MH problem, the value of a well-designed action plan for return to work, the legal and practical issues around adjustments at work, and the benefits of a case management approach to rehabilitation.

- Supporting Day-to-Day Wellbeing. Managers must be equipped with the skills to support the wellbeing of employees daily, and particularly during periods of significant organisational change. Managers need the tools to break unwelcome news sensitively and prepare for the possible psychological impact on employees. Develop regular training to boost management competencies to help reduce psychological harm at work, for example managing emotions, communicating on work issues and managing difficult situations.

June’s blog will focus on managing sickness absence and return to work for employees with mental health illnesses. Meanwhile, if you need help in managing mental health in your organisation, or indeed any other staff issues, do call me on 0118 940 3032 or click here to email me.

The source of this blog is XpertHR.

Wellbeing Initiatives for the Workplace

Recently XpertHR conducted a wide-scale survey of wellbeing initiatives in the workplace, either currently in use or planned. This blog is a condensed summary of their report.

Continue reading